The history of cannabis is closely tied to the development of civilization itself. In fact, many scholars believe that marijuana was one of the first crops cultivated by humans during the Stone Age. These ancient people used the plant for rope, textiles, pottery, food, and medicine.

Emperor Shen Nung

Chinese Emperor Shen Nung (ca. 2737 BC) is believed to have been the first to discover the healing properties of cannabis. We know from ancient Chinese medical texts that the plant was used as an anesthetic during surgeries. It was also used as a treatment for gout, rheumatism, and malaria. Over time, the popularity of cannabis medicine spread throughout Asia, the Middle East, Africa and India.

The Egyptians used marijuana to treat glaucoma and administer enemas. The Greeks employed it to dress wounds and reduce inflammation. The Romans valued it for its ability to alleviate earaches, joint pain and, strangely enough, suppress sexual libido. In India, they combined cannabis with milk to create a concoction known as Bhang. This drink was purported to sharpen the mind, promote sleep, and reduce fevers. It is still used in Hindu religious ceremonies to this day.

Cannabis as Modern Medicine

Queen Victoria

In the 1600’s and 1700’s, the British Empire began to expand throughout Europe and North America. In each new colony, hemp was a mandatory crop for farmers. They used it in the production of various textiles and as a medicine. One of the earliest practitioners of Western medicine was an English scholar named Robert Burton. In his 1621 classic The Anatomy of Melancholy, he promoted cannabis as a treatment for depression.

In the late 1700’s, following his conquest of Egypt, Napoleon brought marijuana back to France. He valued it for its pain relieving and sedative qualities. In the U.S., hemp cultivation was so widespread that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson both grew it on their plantations at Mount Vernon and Monticello. Washington had a particular interest in the medicinal properties of cannabis. We know from his diary entries that he was growing marijuana with a high Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content.

By the 1840’s, marijuana had become a mainstream remedy in the West. Dr. William O’Shaughnessy reintroduced it to British Medicine and prescribed it for muscle spasms, rheumatism, and epilepsy. Queen Victoria is believed to have used it to counteract the pain of menstrual cramps. In France, it was used to treat headaches, increase appetite and as a sleep aid. In 1850, cannabis made its first appearance in the United States Pharmacopeia where it was prescribed for the treatment of dozens of afflictions.

So what happened? How did a plant, revered for millennia around the world for both its functional and medicinal qualities, become so demonized?

Prohibition of Marijuana

“The idea that this is an evil drug is a very recent construction, and the fact that it is illegal is a historical anomaly.”

– Barney Warf, Marijuana’s History: How One Plant Spread Through the World

The story of cannabis prohibition is a cautionary one. It’s a tale of racism, cultural warfare, and political ambition. To understand how we got to this point, we need to revisit the cultural landscape of America at that time.

Towards the end of 1910, the Mexican Revolution began. In the ensuing two decades, more than a million displaced Mexican citizens fled to the United States to escape the conflict. They brought their language, culture, and customs with them. One of these customs was smoking cannabis, which they referred to as “marihuana.” They used it for medical reasons but also smoked it recreationally. The drug became inextricably tied to these new immigrants. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, the fear and resentment of these Spanish-speaking foreigners boiled over. Soon, stories began to spread in the newspapers about Mexican men going crazy from smoking marijuana and killing people.

In the Eastern states, marijuana was linked to the black jazz music scene. Stories about marijuana’s ability to cause men of color to become violent and solicit sex from white women became commonplace.

Perhaps no man played a greater role in the prohibition of cannabis than Harry Anslinger. In 1930, Congress established the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and put Mr. Anslinger in charge of it. Alcohol prohibition was still in effect, but by then it had become an unmitigated disaster. As the head of a fledgling government agency, Anslinger needed a new enemy. He preyed upon the underlying currents of racism and violence to turn marijuana into public enemy #1. These are actual quotes from the man:

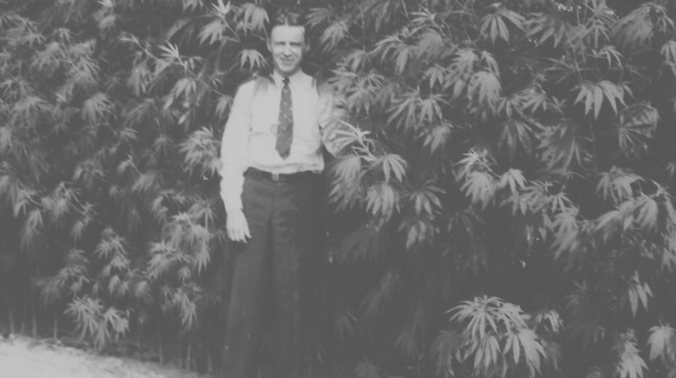

Harry Anslinger

“There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing, result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and any others.”

“Marijuana is the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind.”

He even exploited the nation’s fears of communism when he announced that:

“Marihuana leads to pacifism and communist brainwashing.”

Now exactly how marijuana use could lead to pacifism and also cause users to commit unspeakable acts of violence is a difficult one to explain. But to the newspapers and tabloids, it didn’t matter. They were building an effective campaign to demonize the plant.

At the center of much of this was the legendary newspaperman, William Randolph Hearst. A popular conspiracy theory is that Hearst, with his enormous investments in timber and paper manufacturing, saw hemp as an existential threat to his business and thus helped spread these scurrilous stories about the effects of marijuana. Whether the theory is accurate or not is difficult to prove. What is beyond dispute is that many of the most sensationalized stories linking cannabis to violent acts appeared in newspapers published by Hearst.

In the mid-1930’s the anti-cannabis propaganda machine was in full effect. Reefer Madness informed the nation about how cannabis use would inevitably lead to murder, sexual depravity, and insanity. By the end of 1936, most of the country had enacted laws regulating marijuana. At the same time, new medicines such as aspirin, morphine, and other opioids were beginning to replace cannabis as the painkiller of choice throughout Western medicine. In 1937, over the objections of the American Medical Association, Congress enacted the Marihuana Tax Act. The law still permitted physicians and pharmacists to prescribe marijuana. But it essentially allowed federal lawmakers to tax it so heavily as to make it cost prohibitive.

For a time, Cannabis mostly faded from the American consciousness. But during the political upheaval of the 1960s, more young people began to use marijuana than ever before. LSD and Heroin were also becoming increasingly mainstream. All of this was occurring in a highly visible fashion, against the backdrop of a cultural revolution that was threatening to tear the country apart. The public and the government took notice.

The War on Drugs

In 1970, Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). The law established a single classification system for all narcotic and psychotropic drugs. Each drug was to be assigned to one of five schedules (Schedule I – V) based on their safety and medical efficacy. Before deciding how to schedule marijuana, Congress asked for a recommendation from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Department recommended that Congress appoint a commission to determine whether the use of cannabis resulted in “severe psychological or physical dependence.” Nixon created the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (later known as the Shafer Commission) to study the issue. In the meantime, marijuana was temporarily placed in the most restrictive classification – Schedule I – indicating a “high potential for abuse” and “no currently accepted medical use.”

In 1971, Nixon launched his War on Drugs. In an address to the nation, he stated, “America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse.” The Shafer Commission finally released their report a year later. In it, they unanimously called for decriminalizing marijuana and removing it from the scheduling system altogether. Nixon rejected the recommendation.

John Ehrlichman and Richard Nixon

More than two decades later, former Nixon advisor John Ehrlichman, who spent a year in prison for his role in the Watergate scandal, gave an interview in which he laid bare Nixon’s real motivations for The War on Drugs. Somehow, the contents of that explosive interview remained a secret for 22 years. When excerpts were finally published in 2016, they confirmed the worst suspicions of many – that the War on Drugs was a politically motivated tool designed to destroy Nixon’s perceived enemies, namely the antiwar left and black people.

Nixon was ultimately brought down by his criminal behavior, but many subsequent presidential administrations have continued to pursue his ill-fated course. One hallmark of this has been a more than 700% increase in the U.S. prison population since 1970.

While the prison population has soared, the DEA, under whose authority the CSA scheduling now resides, has continued to ignore the recommendations of the medical and scientific communities, as well as its own people. In 1988, the DEA’s Chief Administrative Law Judge, Francis L. Young, presided over extensive court-ordered hearings. At the conclusion of those hearings, he declared:

“Marijuana, in its natural form, is one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man…To conclude otherwise, on the record, would be unreasonable, arbitrary, and capricious.”

Judge Young recommended that marijuana be transferred to Schedule II. The DEA refused to implement the ruling.

Marijuana Legalization

In the late 1980’s, the AIDS epidemic dominated the national news cycle. Nowhere was its impact felt more strongly than in San Francisco, where gay men were dying in droves from AIDS-related complications. Many of those who were suffering found relief in the form of cannabis. It’s appetite stimulating properties helped counteract the devastating effects of the disease. A series of police raids and arrests targeting this vulnerable population sparked local outrage and helped galvanize public support for a revisiting of the state’s marijuana laws.

In 1996, voters in California approved the Compassionate Use Act. This historic legislation exempted medical marijuana patients and caregivers from criminal prosecution and helped lay the foundation for future laws in other states. Over the next fifteen years, 16 more states would go on to pass medical marijuana legislation.

In 2012, public opinion began a dramatic shift in favor of cannabis legalization. Two more states enacted medical marijuana laws for the first time. More importantly, Colorado and Washington voted to become the first two states to legalize marijuana for recreational use.

Today, 29 states (as well as the District of Columbia) have medical marijuana laws on the books. Eight states have passed laws allowing recreational use. 15 other states have passed medical laws which allow only the use of the non-psychoactive cannabinoid, cannabidiol (CBD).

At the federal level, our laws remain stuck in the past. Over the last three decades, hundreds of peer-reviewed studies have demonstrated marijuana to be a very safe and effective medicine. Yet cannabis, which has never in recorded history caused a single overdose-related death, continues to be classified as a Schedule I drug. Meanwhile, cocaine and prescription opiates, drugs that are widely abused and combine to kill more than 25,000 people in the U.S. each year, are listed under the less restrictive Schedule II classification.

But there are reasons for optimism. In August of 2013, Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole released a Memorandum which provided guidance to the US Attorney’s Office regarding marijuana enforcement. This memo, now known simply as The Cole Memo, called for an end to federal enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) so long as state and local laws are being observed. Then in May of 2014, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives voted to approve the Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment, which prohibits the Department of Justice from using any federal funds to arrest or prosecute medical marijuana patients or providers that comply with their state’s laws. Even the recent appointment of anti-marijuana crusader Jeff Sessions as Attorney General seems unlikely to reverse the significant progress that has been made. With all this positive momentum, hopefully Congress will soon decide to take the final necessary steps to end the federal prohibition of cannabis.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.